How does communication occur? A brief look at the evolution of models that visualize the communication process shows how our thinking about communication has developed:

The linear or transmission model of communication describes communication as a one-way process in which a sender intentionally transmits a message to a receiver (Ellis & McClintock, 1990). This model focuses on the sender and message within a communication encounter. Although the receiver is included in the model, this role is viewed as more of a target or end point rather than part of an ongoing process. We are left to presume that the receiver either successfully receives and understands the message or does not. The scholars who designed this model were influenced by the advent and spread of new communication technologies of the time such as telegraphy and radio, and you can probably see these technical influences within the model (Shannon & Weaver, 1949). [1] Think of how a radio message is sent from a person in the radio studio to you listening in your car. The sender is the radio announcer who encodes a verbal message that is transmitted by a radio tower through electromagnetic waves (the channel) and eventually reaches your (the receiver’s) ears via an antenna and speakers in order to be decoded. The radio announcer doesn’t really know if you receive their message or not, but if the equipment is working and the channel is free of static, then there is a good chance that the message was successfully received.

Although the transmission model may seem simple or even underdeveloped to us today, the creation of this model allowed scholars to examine the communication process in new ways, which eventually led to more complex models and theories of communication.

The interactive or interaction model of communication describes communication as a process in which participants alternate positions as sender and receiver and generate meaning by sending messages and receiving feedback within physical and psychological contexts (Schramm, 1997). Rather than illustrating communication as a linear, one-way process, the interactive model incorporates feedback, which makes communication a more interactive, two-way process. Feedback includes messages sent in response to other messages. For example, a workplace trainer may respond to a point you raise during a discussion. The inclusion of a feedback loop also leads to a more complex understanding of the roles of participants in a communication encounter. Rather than having one sender, one message, and one receiver, this model has two sender-receivers who exchange messages. Each participant alternates roles as sender and receiver in order to keep a communication encounter going. Although this seems like a perceptible and deliberate process, we alternate between the roles of sender and receiver very quickly and often without conscious thought.

The interactive model is also less message focused and more interaction focused. While the linear model focused on how a message was transmitted and whether or not it was received, the interactive model is more concerned with the communication process itself. In fact, this model acknowledges that there are so many messages being sent at one time that many of them may not even be received. Some messages are also unintentionally sent. Therefore, communication isn’t judged effective or ineffective in this model based on whether or not a single message was successfully transmitted and received.

The interactive model takes physical and psychological context into account. Physical context includes the environmental factors in a communication encounter. For example, the size, layout, temperature, and lighting of a space may influence in-person communication, just as the layout and interface of a digital tool may influence digital communication. Whether it’s the size of the room or other environmental factors, it’s important to consider the role that physical context plays in our communication. Psychological context includes the mental and emotional factors in a communication encounter. Stress, anxiety, and emotions are just some examples of psychological influences that can affect our communication. Seemingly positive psychological states, like experiencing the emotion of love, can also affect communication. Feedback and context help make the interaction model a more useful illustration of the communication process.

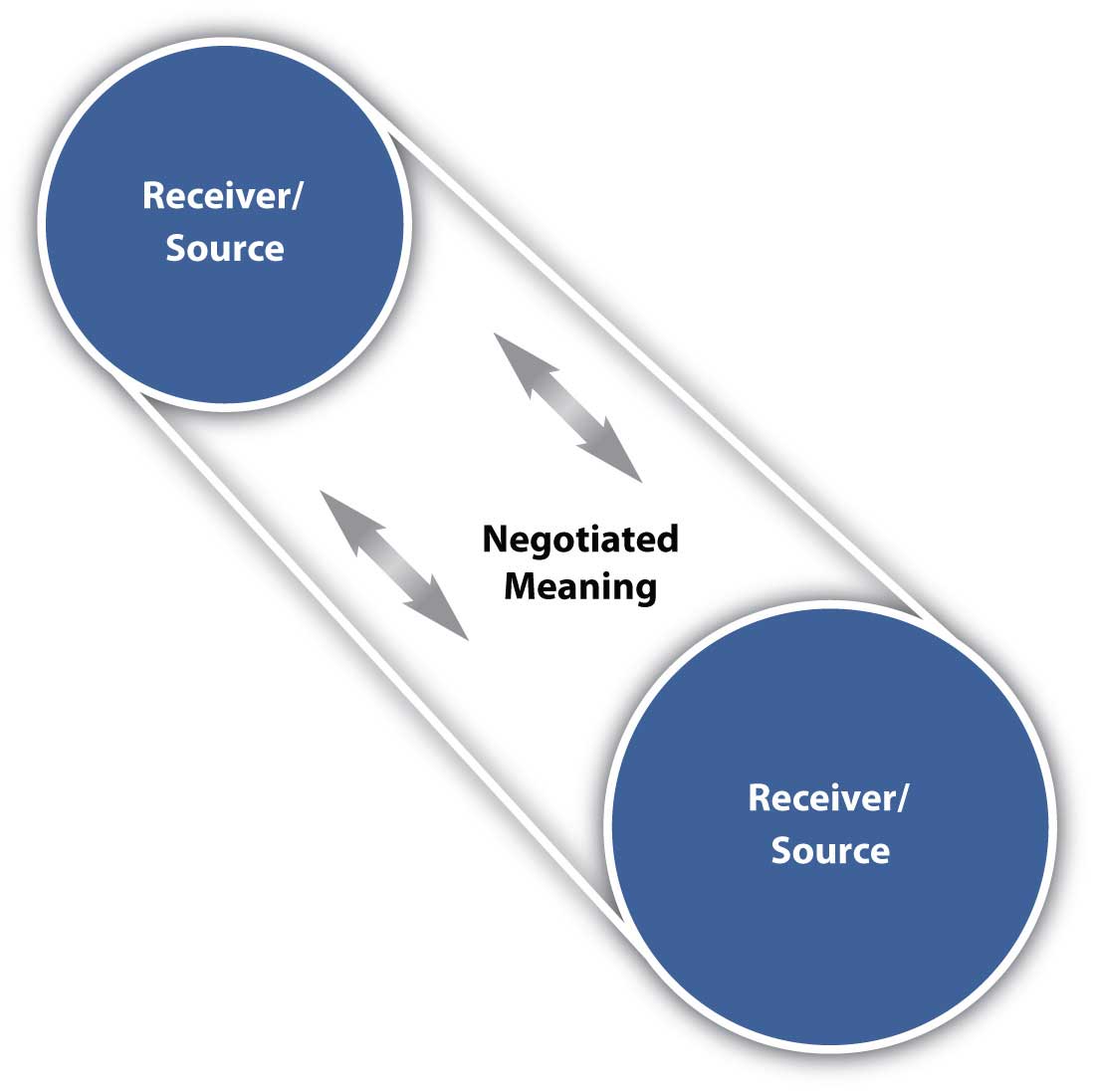

Researchers have examined the idea that we all construct our own interpretations of the message. As a common saying goes, “What I said and what you heard may be different.” The interactive model of communication, from a constructivist viewpoint, focuses on negotiated meaning or common ground reached through participants’ dual roles as sender and receiver (Pearce & Cronen, 1980). [4]

Imagine that you are visiting Atlanta, Georgia, and you go to a restaurant for dinner. When asked if you want a “Coke,” you may reply, “sure.” The waiter may then ask you again, “what kind?” and you may reply, “Coke is fine.” The waiter then may ask a third time, “what kind of soft drink would you like?” The misunderstanding in this example is that in Atlanta, the home of the Coca-Cola Company, most soft drinks are generically referred to as “Coke.” When you order a soft drink, you need to specify what type, even if you wish to order a beverage that is not a cola or not even made by the Coca-Cola Company. To someone from other regions of the United States, the words “pop,” “soda pop,” or “soda” may be the familiar way to refer to a soft drink; not necessarily the brand “Coke.” In this example, both you and the waiter understand the word “Coke,” but you each understand it to mean something different. In order to communicate, you must each realize what the term means to the other person, and establish common ground, in order to fully understand the request and provide an answer.

As the study of communication progressed, models expanded to account for more of the communication process. Many scholars view communication as more than a process that is used to carry on conversations and convey meaning. We don’t send messages like computers, and we don’t neatly alternate between the roles of sender and receiver as an interaction unfolds. We also can’t consciously decide to stop communicating because communication is more than sending and receiving messages. The transaction model differs from the transmission and interaction models in significant ways, including the conceptualization of communication, the role of sender and receiver, and the role of context (Barnlund, 1970).

The transaction model of communication describes communication as a process in which communicators generate social realities within social, relational, and cultural contexts. In this model, we don’t just communicate to exchange messages; we communicate to create relationships, form intercultural alliances, shape our self-concepts, and engage with others in dialogue to create communities. The transaction model thus views communication as a powerful tool that shapes our realities beyond individual communication encounters.

The roles of sender and receiver in the transaction model of communication differ significantly from the other models. Instead of labeling participants as senders and receivers, the people in a communication encounter are referred to as communicators. Unlike the interactive model, which suggests that participants alternate positions as sender and receiver, the transaction model suggests that we are simultaneously senders and receivers. This is an important addition to the model because it allows us to understand how we are able to adapt our communication—for example, a verbal message—in the middle of sending it based on the communication we are simultaneously receiving from our communication partner.

The transaction model also includes a more complex understanding of context. The interaction model portrays context as physical and psychological influences that enhance or impede communication. While these contexts are important, they focus on message transmission and reception. Since the transaction model of communication views communication as a force that shapes our realities before and after specific interactions occur, it must account for contextual influences outside of a single interaction. To do this, the transaction model considers how social, relational, and cultural contexts frame and influence our communication encounters.

Imagine you are in Lebanon, a high context culture. When you are introduced to the professionals with whom you are meeting, everyone is standing outside of a meeting room. Another professional arrives late, after the meeting has started and everyone is seated around a conference table. You sense a hesitation in his words and body language as you are introduced. You remember seeing that a Lebanese colleague with whom you have worked in the past always stood when greeting someone; you stand up to introduce yourself, and see a change in demeanor in the late arrival. You realize, through this non-verbal transaction, that standing up to first meet a person is a sign of respect that is important in this particular culture.

Knowing about the evolution and different models that describe communication processes should help you as a professional communicator, to develop fuller insight into what happens during a communication and how others may react to and process information.

[1] Shannon, C. and Weaver, W. (1949). The mathematical theory of communication. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press.

[2] Schramm, W. (1997). The beginnings of communication study in America. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

[3] Barnlund, D. C. (1970). A transactional model of communication in K.K. Sereno and C.D. Mortenson (Eds.), Foundations of communication theory (pp. 83-92). New York, NY: Harper and Row.

[4] Pearce, W. B., & Cronen, V. (1980). Communication, action, and meaning: The creating of social realities. New York, NY: Praeger.

Licenses and Attributions CC licensed content, Shared previously